Problem: As described by Goldman Sachs’ Global Market Institute, “The U.S. personal saving rate has declined from 10.8 percent in 1984 to zero in 2005. The national saving rate, which includes government and business savings, is the lowest among the G-20 countries and has decreased significantly in recent decades. These low levels of saving generally suggest lower growth rates of income and standards of living in the future.” Moreover, the rich tend to save more, as reported by the Federal Reserve: “Using a variety of instruments for lifetime income, we find a strong positive relationship between personal saving rates and lifetime income.”

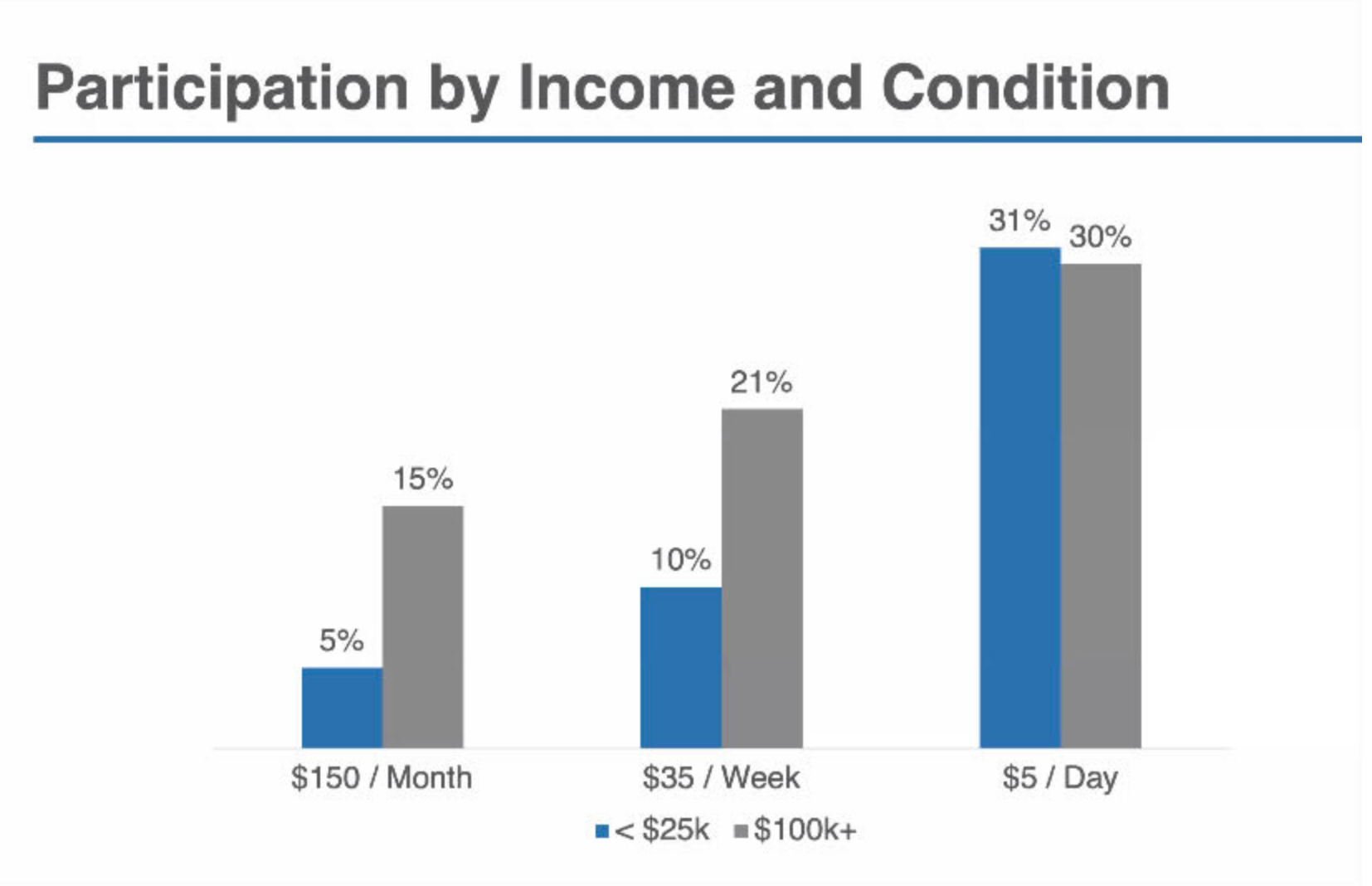

Solution: Today I had the pleasure of attending a lecture by Hal Hershfield titled “Democratizing Savings.” At this talk, Hal described the differences in savings rates between wealthy Americans (those making $100k or more a year) and less well-off Americans (those making less than $25k a year). Based on past literature, researchers have shown that lower-income individuals tend to save less. His team wanted to investigate whether reframing savings could incentivize lower-income individuals to save more.

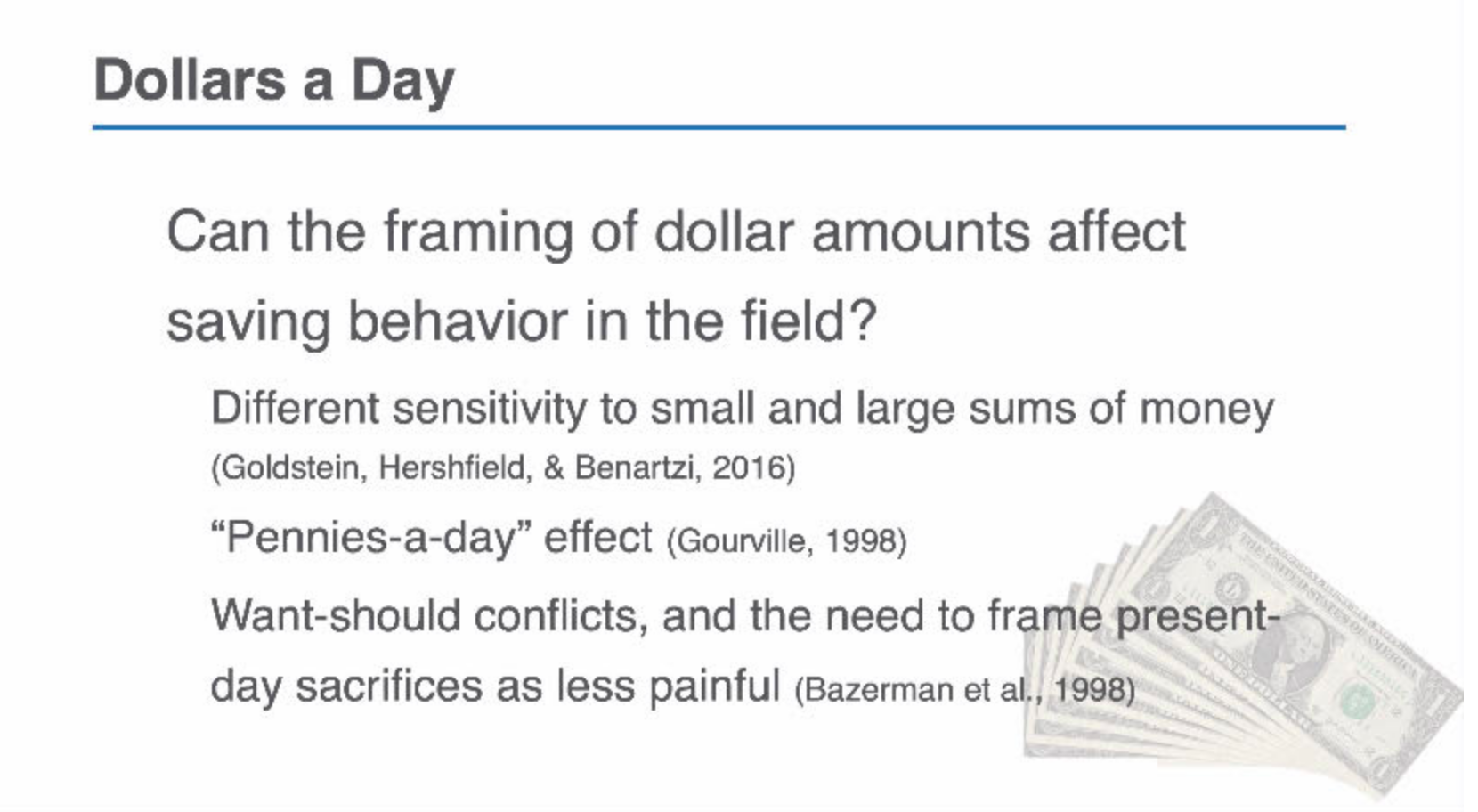

To do this, they created three conditions to encourage people to save $150 a month. In condition 1, participants saved $5 a day every day for a month; in condition 2, participants saved $35 a week every week for a month; and in condition 3, participants saved $150 once a month. The question to answer was “how does reframing contribution frequency affect on-boarding and retention in these programs over time?” Results from Hal’s research are below via slides he shared. A second experiment encouraged people to save $30/month either weekly or in a lump-sum every month.

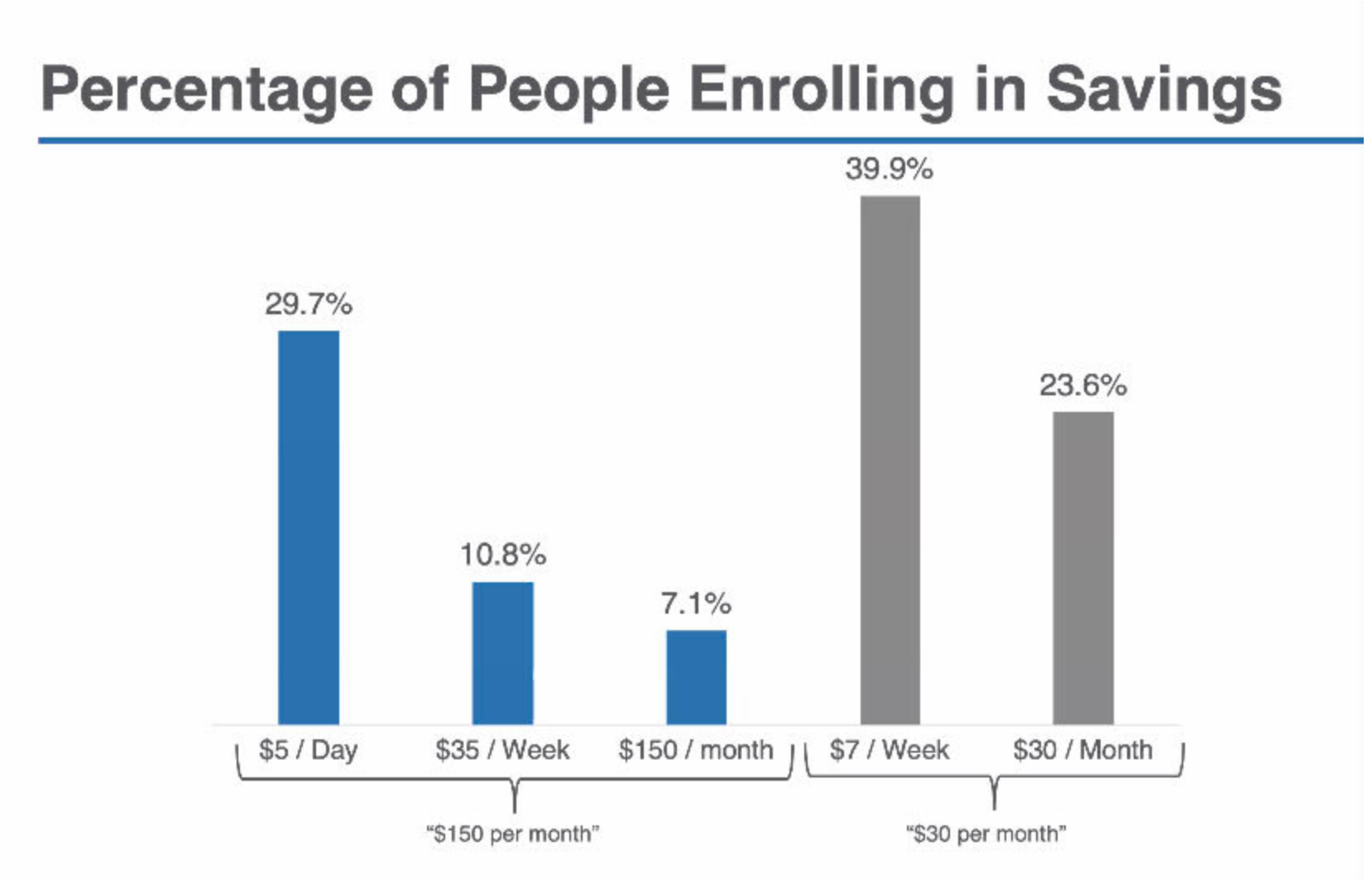

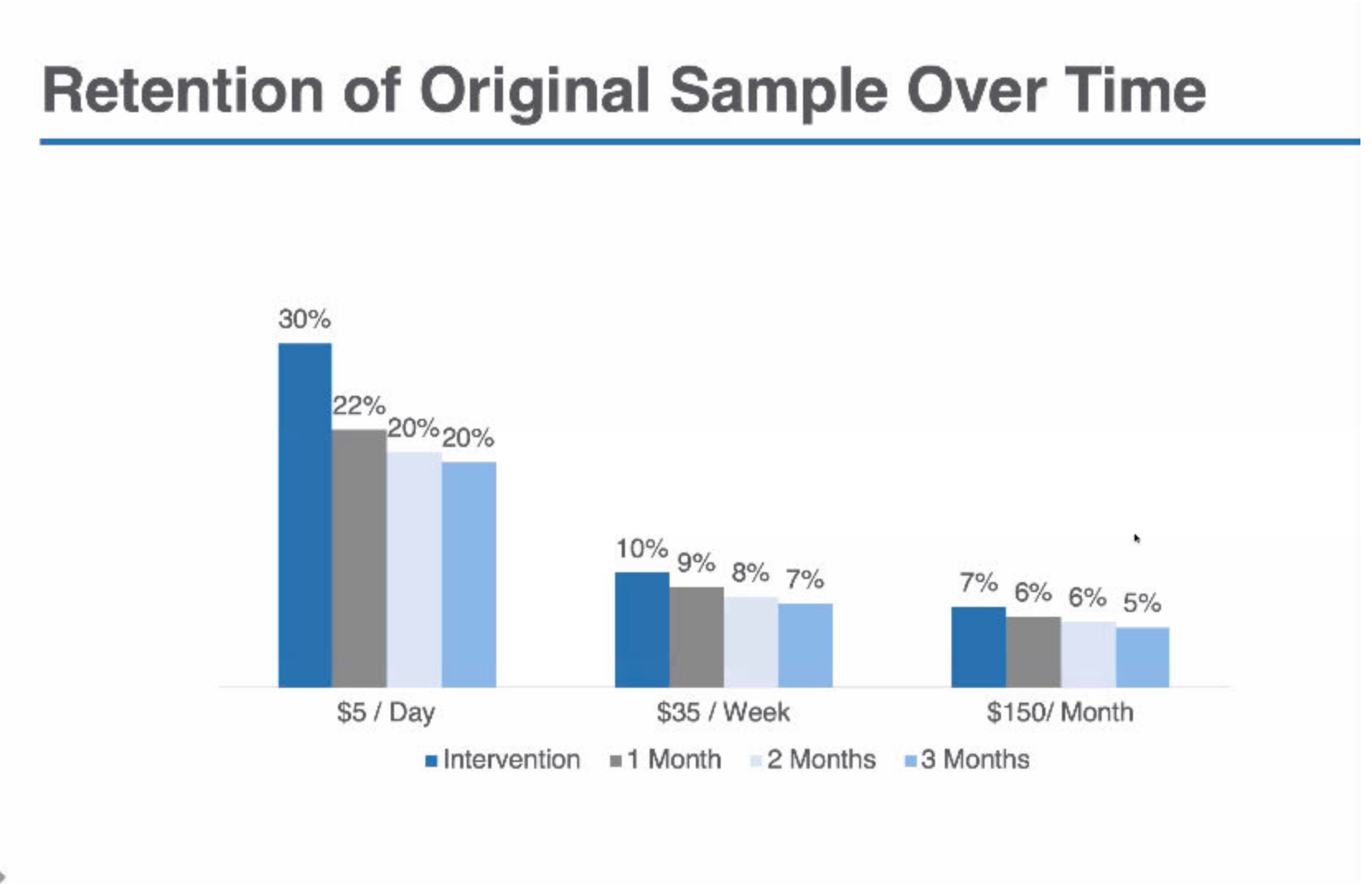

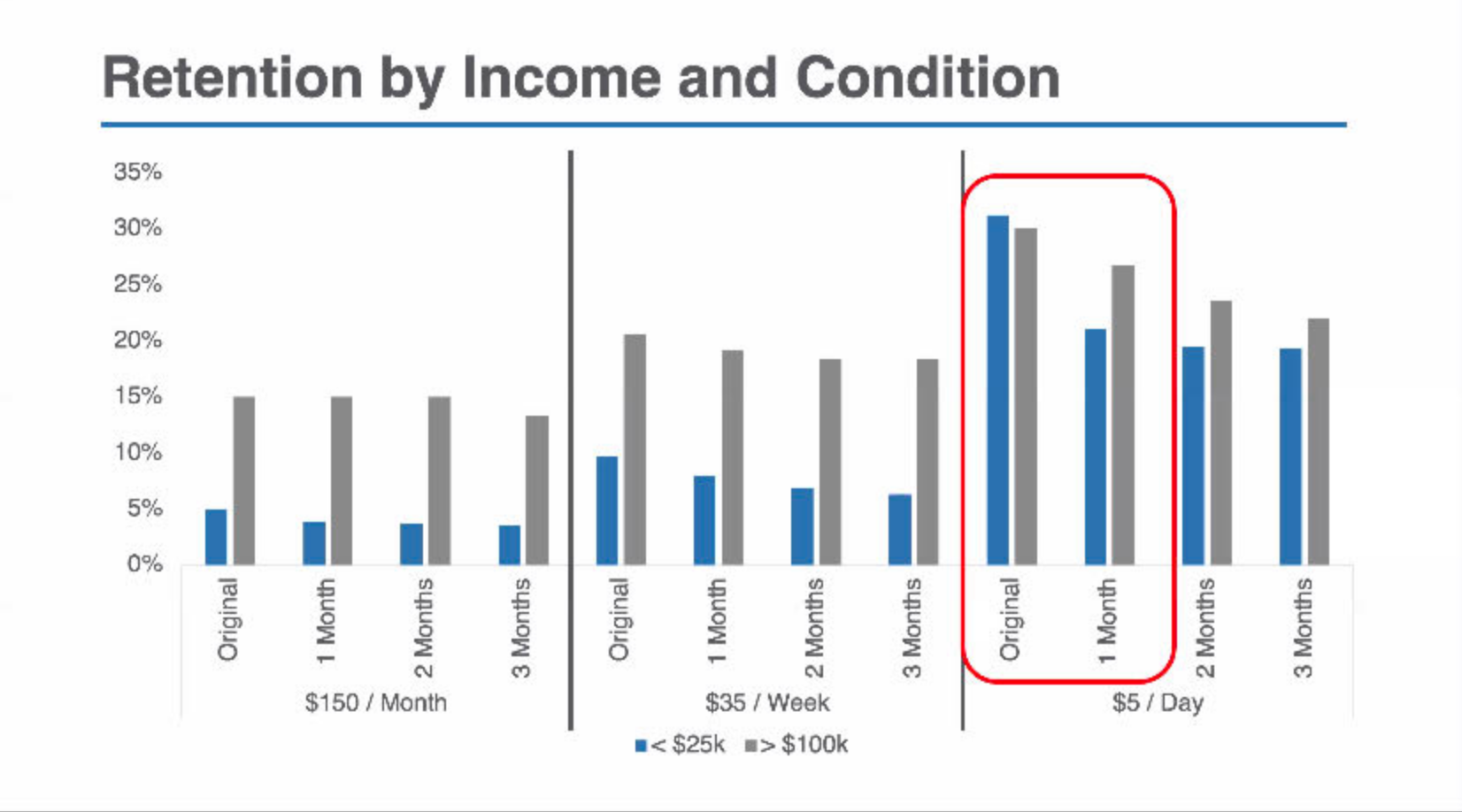

The results of the study (shown in the images above, and on our website here) was that the percentage of people enrolling in these savings programs increased dramatically in the more piece-meal conditions. 29.7% of people enrolled to save $5/day whereas only 7.1% of people enrolled to save $150/month (what’s interesting is the end result is the same in both conditions (saving $150). While long-term retentions was slightly lower in the daily condition when compared to the weekly or monthly conditions, the overall number of people enrolled in the program on the daily condition was still much higher than the weekly or monthly condition.

When the data is segmented by income bracket we see an even more interesting phenomenon: lower-income individuals are more likely to save $150 a month when it is split up over daily payments than when it is split up into monthly payments. Moreover, while there is a larger drop-off from month 0 to month 1, long-term retention in the low-income/daily condition is higher than any other condition.

This business would build mobile banking for underserved, underbanked, and low-income clients to inspire better money habits.

The 2017 FDIC Survey estimates that “6.5 percent of households in the United States were unbanked in 2017. This proportion represents approximately 8.4 million households. An additional 18.7 percent of U.S. households (24.2 million) were underbanked, meaning that the household had a checking or savings account but also obtained financial products and services outside of the banking system.” The business would focus on this segment of the market.

Monetization: A traditional model of banking: investing “float dollars” that are put in savings.

Contributed by: Michael Bervell (Billion Dollar Startup Ideas)